Seeds of change: Youth take center stage at Colorado Food Summit

The small room on the second floor of the Stockyards Event Center buzzed with excitement as dozens of high schoolers waited to hear what question they would be tested on next.

“I’ll take ‘Sourcing your Colorado specialty’ for 300!” shouted a voice from the back, eager to prove what they had learned during a day filled with workshops covering the ins and outs of Colorado’s dynamic food system.

“This root crop is typically grown in the San Luis Valley of Colorado,” read Sydney Cure, a freshman soil and crop sciences student at Colorado State University, before scanning the room during the high-energy game of Jeopardy.

Students shot their hands into the air, fingertips stretching wide, as others furiously flipped through pages of scribbled notes covering conversations with farmers and topics from food waste to community collaboration, and how to impact change.

“What are potatoes? I mean, what is potatoes?”

“You got it!” responded Cure.

Engaging youth to shape the future of Colorado ag

This was Cure’s second year at the Colorado Food Summit, hosted by CSU’s Food Systems Institute. However, it was the first year where she – and 12 of her peers – were able to step into paid positions helping plan the event.

The group of young leaders, made up of high school and college students, organized a series of youth-focused sessions, as well as social opportunities for the students to connect and learn about each other’s lives.

“We wanted to talk about the agriculture we’ve seen our entire lives,” said Cure, who hails from Eastern Colorado. “We also wanted our workshops to be active and interactive because a whole day of presentations is exhausting.”

With sponsorship from the Colorado Department of Agriculture’s NextGen Ag Leadership Grant Program, the youth leaders were able to help cover the costs so that 65 young participants could attend the summit and be part of the conversation about how to shape the future of Colorado’s food systems.

Gaining new perspectives

For Zora Malone, who has grown up in Pueblo, the youth-organized sessions gave her the opportunity to ask questions directly to agricultural producers, which she hadn’t had the chance to do before.

“It was interesting to hear the perspectives of farmers because there’s a lot of blame and we don’t understand why decisions are made, and I’m thankful I was able to hear it from them,” said Malone as part of a group activity reflecting on the experience.

“I’m starting to see more of a future for myself in this system.”

– Zora Malone

One of those farmers offering a peek behind the curtain was Sarah Jones, who helps run Jones Farms Organics, a fourth generation family-owned organic potato farm in the San Luis Valley.

“Hearing what students questions are is so educational for me,” said Jones. “Oftentimes they’ll have heard about things like organic produce or GMOs, but don’t know what the terms really mean, and I love being able to address that.”

Jones told the students that having a career related to agriculture doesn’t mean your only option is working out in the field or on a combine.

She explained how for her business, sales and communication play a huge role, helping change the public’s understanding of the products they buy and ultimately reshaping consumer demand, which is at the heart of our food systems.

Malone listened attentively.

“I’ve met farmers before, but I’ve never been able to look into the processes behind the scenes, so I’m trying to learn as much as I can,” she said.

Living in Pueblo, Malone has become familiar with what it looks like for families to struggle with food access, as the region has one of the highest rates of food insecurity in the state.

In Pueblo city schools, 74% of students qualify for free or reduced lunch, twice the state average.

In Pueblo County, more than 40% of residents live in low-income areas with little access to nearby supermarkets, limiting their options for healthy, affordable food.

Malone attended the summit with her mom, Cheryl Anderson, who is the executive director of a non-profit that focuses on empowering communities through horticultural education and resources.

“I’m inspired by what my mom does and I’m starting to see more of a future for myself in this system,” said Malone, who is interested in going into city planning. “I’ve just noticed there are a lot of ways you can be a problem solver. You may not be a farmer, but you can help farmers feed people.”

Although there are countless directions her future career could take her, Malone is leaving the summit inspired by her peers to take concrete action to help her community: she plans to start a food pantry at her school.

Bringing their values to the table

“Our youth see things differently,” said Becca Jablonski, an associate professor at CSU who also serves as an Extension economist and co-lead of the University’s Food Systems Institute.

“We came up with the agenda for the summit using a regional engagement process, where we went through all of these different agendas and meeting minutes and talked to regional stakeholders to understand opportunities and challenges to elevate to the state level,” said Jablonski. “The young leaders had their own process.”

“They identified food waste as a major issue,” she continued. “The only food waste session at the summit was led by them.”

“Just a few days ago, the USDA, EPA and FDA released their first ever national strategy to reduce food waste. So, our young leaders were ahead of the curve identifying this key topic,” Jablonksi said.

The three young leaders responsible? Taliah Martinez, Miguel Torres and Angelique Pino.

Reducing food waste

At Torres and Pino’s high school in the heart of Colorado Springs, 93% of students qualify for free and reduced lunch. Both have felt the need to help, volunteering with their school’s pantry and distributing food to students and their families on a weekly basis.

So, when they began researching food waste and learned that roughly 30%-40% of the food produced in the United States is never eaten, they wanted to do something to help change the numbers.

“We all know those guilty feelings of throwing away food could be stopped.”

– Miguel Torres, youth leader

The group’s presentation on Scrappy Cooking focused on how consumers can reduce their food waste by being more conscious about meal planning, getting creative with recipes and better understanding how much effort goes into producing food.

“We had to study this ourselves because we weren’t taught it, it’s something you have to notice, even in your own home,” Pino said.

Increasing awareness of community challenges

For fellow youth organizers Mylo Lovejoy and Jorey Billings, who have grown up working alongside farmers and ranchers, the challenges faced by producers across the state aren’t abstract, they’re felt throughout their small town of Campo, where their local high school has 10 students.

“You drive down the road and see crops that are dying right next to good crops, and you wonder why,” said Lovejoy, whose curiosity has led him to explore some of the most difficult topics in Colorado agriculture.

“You start to learn about the lack of rain, and the controversy between farmers who have to rely on rain and producers who will put in sprinkler after sprinkler and suck up all the water,” added Billings.

“Some people don’t think about the long-term impacts.”

– Mylo Lovejoy, youth leader

In Campo, agricultural producers sit on the edge of the Ogallala Aquifer, and many rely on the ever-shrinking body of groundwater to bring life to their grain crops and hay.

“I’d really like to talk to people about it,” said Lovejoy, who hopes to go into engineering and create innovations, like more efficient ways to water crops, that could help the producers in his hometown.

“Some people don’t think about the long-term impacts,” Lovejoy said, recalling dry summers where massive clouds of dust would rise from the horizon and darken the skies above them, a stark reminder of the devastation that Baca County faced during the Dust Bowl nearly a century ago.

Baca County dust storms, 1930s

Baca County dust storms, 1930s

Baca County dust storm, 2023

Connecting problem solvers

Monique Marez, a food systems consultant based in Pueblo, has been coordinating the efforts of the Colorado Food Summit’s youth leaders who applied and were accepted to the group. The students first connected online as a team during the summer.

“In the first sessions they were asking each other, ‘Who are you and what do you care about? What are the challenges in your community? Here are the challenges in mine,'” recalled Marez.

“They found common problems, broke into interest groups and began designing their sessions and identifying speakers they wanted to bring in,” she continued. “They legit have done it all.”

The group worked together online every other week leading up to the summit, where they were able to meet each other in person for the first time

“They all have different perspectives, but none of them are satisfied with their food systems,” explained Marez, citing shared concerns about food access, waste, challenging economics for first generation farmers, and the growing number of people who don’t understand how food gets from the farms to their plates.

“It was my job to say, ‘What would you do? Okay, let’s do it,'” said Marez. “I wanted them to have the opportunity to know that they can solve problems.”

With that freedom, they put on sessions that provided youth a holistic view of Colorado’s food systems and highlighted successful efforts to expand food access and equity, imploring each other to return to their communities to share what they learned.

They also proved the youth belong at the grown-ups’ table.

Colorado Food Summit

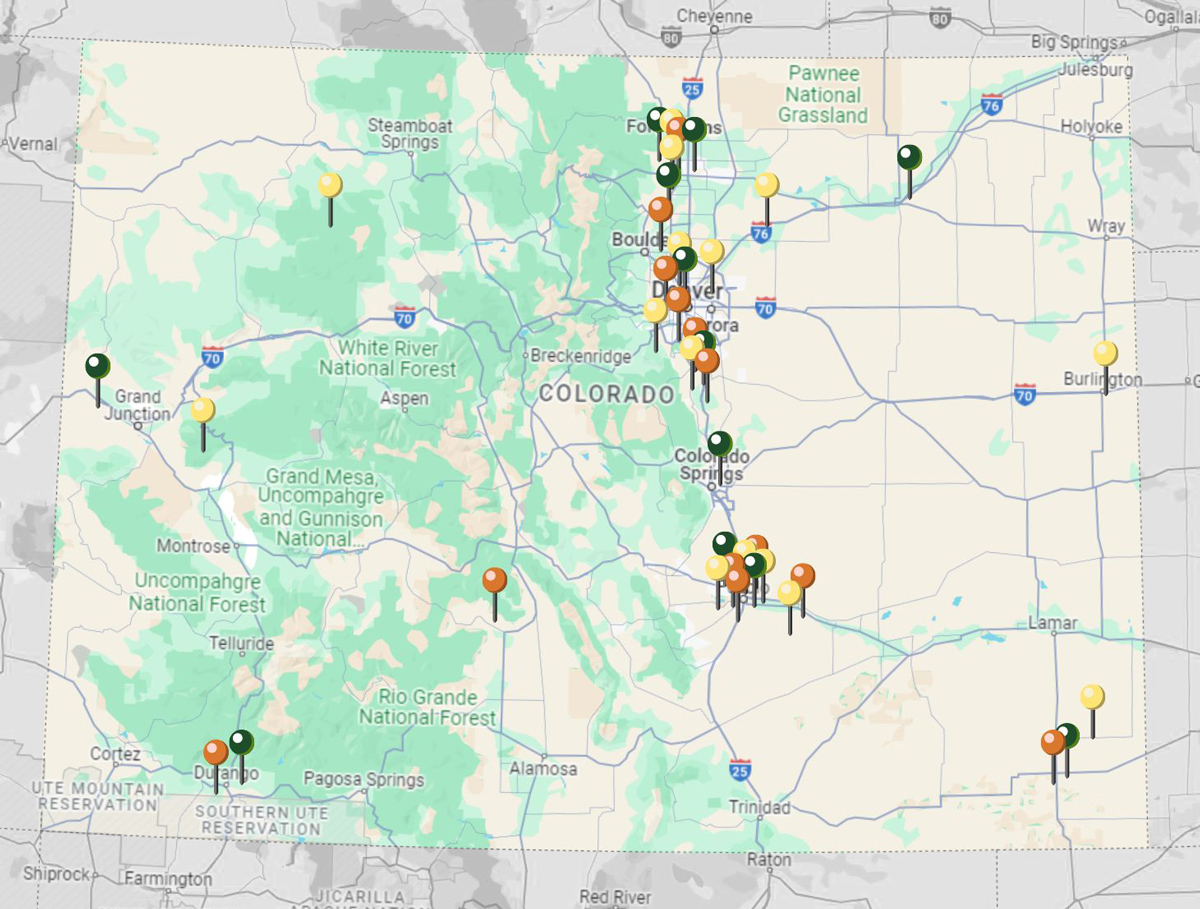

The 2023 Colorado Food Summit brought together over 700 food and agriculture stakeholders from across the state to help build shared understanding of the complex opportunities and challenges facing our food and agriculture systems.

NextGen Ag Leadership Grant Program

The Colorado Department of Agriculture's NextGen Ag Leadership Grant Program provides grants to agricultural organizations and educational institutions that support developmental and training opportunities for the next generation of agriculturalists.

Colorado’s food and agriculture industry is broad and diverse. This program is geared toward not just future generations of farmers and ranchers, but also people trained in the biosciences, nutrition, meat science, veterinary science, agronomy, soil health and conservation, engineering, food safety, technology, product development, marketing, and logistics.